Frustrated by Coronavirus Conspiracy Theories In the Black Community? Here's What Three Experts Think.

"We want to protect each other as much as possible. And I think honing in on that is really important."

Speak Patrice Presents: Coronavirus News for Black Folks is an independent newsletter that aims to empower our community by sharing coronavirus (COVID-19) news and stories as they relate to the Black Diaspora.

Please consider (1) clicking that itty bitty ❤️at the top of this email next to my name to “like” us, (2) subscribing, and (3) supporting this newsletter by sharing it with friends and family.

(Photo by Timi David on Unsplash)

"Oh, I ain't worried about that shit! Y'all get that shit, Black people don't.” — an unidentified woman to a Baltimore police sergeant after he appears to intentionally cough on her.

One of the first falsehoods of the new coronavirus COVID-19 was that Black people were immune to it.

These beliefs likely stemmed from initial reports in mid-March of there being very few coronavirus cases throughout the African continent. Headlines like “With only three official cases, Africa's low coronavirus rate puzzles health experts” and “Coronavirus enigma: Experts ask why Africa seems to have few cases” seemed to give some people the impression that there was something exceptional, if not magical, about African nationals’ purported resistance to this disease, so why not their descents throughout the Diaspora, too?

Words like “puzzle” and “enigma” only sweetened this possibility. White people — presumably, given the history of racial disparities in the field of science and in newsrooms — seemed unable to reconcile that they were suffering and dying at rates disproportionate to Black people living in Africa of all places.

“Hoes mad,” tweeted Ivie Ani, culture writer and former OkayAfrica music editor. Nearly 300,000 Twitter users agreed.

Later that month, the rapid community spread of this disease and the ramped up concern of a growing pandemic led to subsequent reports of confirmed coronavirus cases and deaths throughout Black communities in the United States, the United Kingdom, Jamaica, Nigeria, and beyond.

These reports effectively stifled the growing myth of Black immunity. But claims that COVID-19 was created and disseminated by the U.S. government, China, or radiation from 5G cellular data network, combined with a longtime distrust of the government and national health care systems rekindled any remaining bits of skepticism. While these conspiracy theories are certainly not specific to Black people (for every Tyrese and Keri Hilson, there’s also a John Cusack and Woody Harrelson), the potential for becoming infected or dying from COVID-19 as a result of misinformation is much greater within the Black community due to preexisting health disparities that already lead to higher cases of COVID-19 cases and deaths.

In a recent a panel (held by this newsletter) on coronavirus conspiracies in the Black community, Patricia A. Turner, a Dean and Vice Provost at UCLA and author of I Heard It Through the Grapevine: Rumor in African-American Culture, noted the complicated nature that makes these theories and others like it especially tenacious when it comes to Black people, particularly those in countries with histories of systematic racism and discrimination against their community.

The forced sterilization of the Relf sisters and other impoverished Black women in the south and COINTELPRO, the FBI’s secret counterintelligence program aimed at destroying the Black Panther Party movement and other domestic groups deemed radical, are just a few of the undisclosed plans conceived and implemented by the historically white federal government against Black communities that seem too preposterous and nefarious to be (when, in fact, they are) true.

The power relationship between Blacks and whites has been profoundly unequal from 1619 until the present, so it's not surprising that we respond to that by developing and communicating and sustaining narratives that speak to that larger culture,” Turner said.

“[While conducting interviews for my book], the people who told me they believed that AIDS was invented in a laboratory as a mechanism for eliminating African-Americans or Africans from the world would substantiate that belief by talking to me about the Tuskegee experiment,” a study conducted by the United States Public Health Service from 1932 to 1972.

To observe the effects of untreated syphilis on the human body, health professionals enrolled 600 impoverished Black men sharecroppers from Macon County, Alabama into what they claimed would be a six-month study under the guise of providing free health care, meals, and burial insurance from the government. Not only were all patients misinformed about the highly unethical medical procedures and experiments they agreed to, but also the doctors and scientists withheld diagnoses, treatment, and information about penicillin from the men for forty years, with many patients dying from the disease and transmitting it to their partners and new born children.

“So [the Tuskegee syphilis experiment] was a very real thing that people use to substantiate something that hasn’t proven to be [true],” Turner said. “One of the lines that I have in my book is ‘Just because you're paranoid doesn't mean they're not out to get you.’”

Herein lies the conundrum for many people whose loved ones and acquaintances spout coronavirus-related conspiracies and equally misinformed and unverified remedies in the group chats and phone calls: How does one acknowledge the history of unlawful and harmful agendas aimed at the Black community, while also combating a pandemic that requires well-informed awareness and thrives on the same distrust that incites these coronavirus conspiracies? And what language is used so as not to shame or isolate the same person one aims to love and protect?

Writer Amber Butts explored similar questions in an op-ed essay for RaceBaitr titled, “Even when Black conspiracy theories are misguided, they are not nonsensical,” touching on a controversy surrounding the 2019 fatal shooting of rapper, entrepreneur, and philanthropist Nipsey Hussle. Some believe the artist’s murder was connected to a pharmaceutical company because of his work on a documentary about Alfredo “Dr. Sebi” Darrington Bowman, an herbalist and self-proclaimed healer who claimed he had discovered natural cures for cancer and AIDS.

In her piece, Butts revealed how her late grandmother, “one of the biggest conspiracy theorists [she] knew,” believed in both misguided theories and substantiated facts grounded in climate justice and the lesser-regarded environmental racism. This relationship along with her experience as an Oakland-based grief worker, educator, and community organizer motivated Butts to consider the culture and history of conspiracies in the Black community from a place of sensitivity, empathy, and consideration.

“I recently received a text from my uncle in our family group text,” Butts said at the Coronavirus News for Black Folks panel on coronavirus conspiracies in the Black community. “The message essentially said, Make sure there are no cell phones, laptops, any electronic equipment near you because at 3:30 AM folks are going to be exposed [to radiation].”

Her uncle had told the family that he got this message from a friend her trusts and that he just wanted everyone to be as safe as possible.

“I think, at the core of my uncle’s message, he was trying to keep us safe and give us tools to be able to arm ourselves and be prepared because our lives as Black folks is all about like struggle, survival, or [at least] those are the narratives that were told,” Butts said. “And so we want to protect each other as much as possible. And I think honing in on that is really important.”

The inherent danger in misinformation and false claims is not lost on Butts, who acknowledged the importance of questioning and verifying a conspiracy theory by referring to her friend's’ family members who ultimately “lost their lives” prioritizing unsubstantiated medical advice from Bowman over their own physicians. This blind belief in health care coming from a more familiar and self-validating source is also what worries Turner, who spoke to the double edged nature of these conspiracy theories that can double as “tools of resistance” and weapons for self-harm.

“[During the AIDS outbreak in the 1980’s and 90’s], a rumor proliferated in the Black community that Black men with AIDS should not take the new antiretroviral medication AZT because scientists had put something in it that accelerated the rate at which their bodies would deteriorate from AIDS,” Turner recalled.

“Medical professionals were telling me, at the time, ‘Here we have a therapy that could be helpful to individuals and they were shunning it and getting sicker and sicker.’ So I worry about that when we get a vaccine for the new coronavirus, people who will be suspicious of that and say that that's actually going to put toxins in our body or accelerate the rate at which we get a disease.”

The lack of certainty surrounding the pandemic and its implications on the future of our society as a whole combined with the rapid, fatal spread of this new coronavirus disease and the necessary social distancing measures have generated a space ripe for conspiracy theories that seemingly border on obsession. People are at home, whether alone or with the same individuals for weeks on end, Googling and tweeting and researching. For many, that involves filling the role of information typically reserved for the media, that means copy and pasting every and any possible causes and solutions for the bewildering entity endangering them and their loved ones.

Dr. Racine Henry, a licensed New York City-based therapist who specializes in psychotherapy “as it relates to our history in this country as Black people,” spoke to the potential underlying psychological factors influencing people to believe coronavirus conspiracy theories.

“For a Black person in America, there've been so many things that have happened [where] either the truth sounds like a conspiracy theory or there is no real clear truth: the killing of our political leaders, the ways in which Black people have been tested on and used as Guinea pigs for certain things,” Dr. Henry said. “So I don't doubt people, especially Black people, people of color for believing in conspiracy theories.”

However, she continued, that does not negate the possibility of serious health implications if these theories “go too far” and begin to impact one’s mental and physical behaviors. “There's a link [between the physical, mental, and emotional] that we as a society tend to neglect and ignore and undermine,” Dr. Henry explained. “So if these conspiracy theories lead to high levels of stress or anxiety, you're going to have physical symptoms as well.”

She pointed to examples of self-harm, such as excessive ‘emotional eating,” as behaviors that might be triggered by one’s belief system, while also emphasizing that her duty as a professional was to diagnose others based on their ability to function in a positive and healthful way and not on her own personal definition of normality.

As for those loved ones on the receiving end of those misinformed coronavirus theory text messages, both frustrated and concerned that their family and friends are not well-informed about this fatal disease, Dr. Henry agreed that these exchanges can often be “emotionally draining” and suggested setting boundaries: “Maybe it's a text you send saying, ‘Listen, I care about you, and I love you, and if you need something, let me know. But until this is over or until we're in a different space, I can't speak to you every day or often because of how it impacts me and I have to take care of myself.’”

Other options include making a choice to simply end the phone conversation when a loved one starts talking about topics that negatively affect your emotional state or not answering your calls with a person until you’re in a better space to have that conversation and give them the time they’re seeking.

“We all have to really focus on our mental, emotional health and be sure that we're doing what we can to keep ourselves healthy,” she said. “So if that means separating from people right now, if that means taking more time for you or limiting what you do and how you do it, then you have to do that.”

Creating space for one’s self in this way during an already extremely isolated time might produce feelings of guilt and perpetuate even more stress and anxiety, to which Dr. Henry advised asking whether that person or people can truly be controlled and whose “job” it is to keep that person safe.

“You're going to spend so much time trying to keep them safe or keep them at home, possibly doing things that don't feed or help you and that put you at risk, and then you're going to develop resentment towards that person,” Dr. Henry said.

“So I think you can express your concerns, outline what you think is realistic or feasible for that person, what is healthy for that person, and then you have to let them do what they want to do.” Exceptions can be made for dependents, she added, whether that be a child or a person whose physical and mental faculties are compromised.

As the Black community navigates this unprecedented time, all three panelists underlined the importance of intersectional perspective and compassion, whether for one’s self or others. For Butts, one of the realities of her world has always been that paranoias held by her grandmother, her community, and herself have held some form of legitimacy.

“I [consider myself] lucky to be able to think about these conversations and extend grace to both myself and folks who don't trust our current government,” she said. “That is something I'm always uplifting, that creativity and imagination, the ability to actualize newer worlds and also resist the ones that are currently impacting our own.”

Quotations have been edited and condensed for clarity.

If you’re suicidal, we recommend contacting the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline toll-free at 800-273-8255.

Additional hotlines addressing suicide and other crises — including AIDS information, alcohol, child abuse, domestic violence, and sexual assault — are available at PsychCentral.

REAL QUICK!

Coronavirus News for Black Folks was recently featured in Nieman Lab and Blavity. Thank you for the continued support everyone!

Here’s a quick anonymous survey you can take to help me help you stay best informed and engaged with this newsletter:

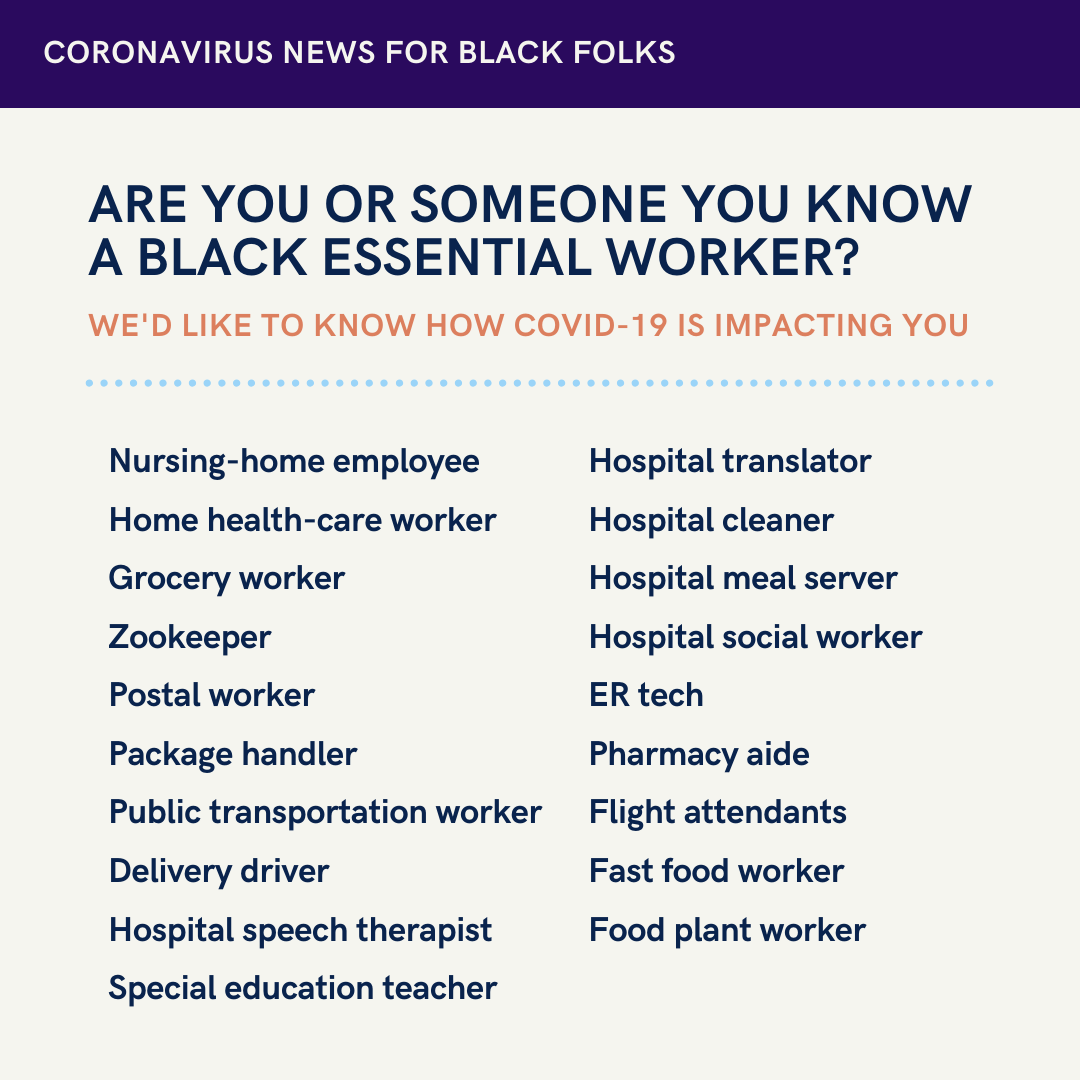

Do you know a Black person in the U.S. or abroad who works on the front lines of the pandemic? If so, please submit your story for a potential feature in an upcoming newsletter post. We’re especially interested in hearing from individuals whose professions and jobs have yet to be spotlighted in the media.